As you may be familiar in my endeavors as a recording artist. I & I released Rastamerika 12-12-12. Ganjah ah ago, or Ganja ah go was the only music video from that album. It disappeared from Vimeo years ago for reasons unknown. However, give thanks for Jah Bless irie vibes! This video is a journey through Dogon arts of West Africa, the travels of Mansa Musa in Central Africa, Egypt to Mecca, and to East Africa with His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia. Baby Thrive and his lion make a few appearances. Let’s see if you can spot Jah T. See’en. Enjoy the visuals of Ganjah go 2025. Bless

Got the munchies?!? Getaway Cafe is the place to be

Getaway Cafe is right across the street from the UCR soccer and softball fields on Canyon Crest Dr. It’s a dim lit sports bar with pool tables and a patio. They serve burgers, pizzas, wings, sandwiches, carne fries, burritos, and other delicious munchies eats.

When I returned to UCR to complete my undergraduate studies in Ethnic Studies. I made it a thing to start each quarter with a quick bite to eat while I was in between classes or finished for the day at Getaway Cafe. This time served me as time to plan the next three to four months of my upcoming workload. My work schedule was already planned around lectures and discussions. I work as a line cook in a corporate kitchen that focuses on production. Which is nothing being that I do have some skills in the kitchen. I am also a graduate of the Riverside Culinary Academy. Where I earned an Associate of Science degree in Culinary Arts from Riverside City College in 2021.

September of 2024 the owner of Getaway Cafe Shaun called me and asked if I was still looking for some kitchen work. I said yes. Shaun worked around my schedule and allowed me to put my skills to use. It was a great experience. I say all of that to say this. Getaway Cafe is not only a place that I would work at as a cook. But I would also eat there when I am hungry or just have the munchies and want to watch the game with a brew. Getaway Cafe is the spot. Get there. Tell them Thrive sent ya!

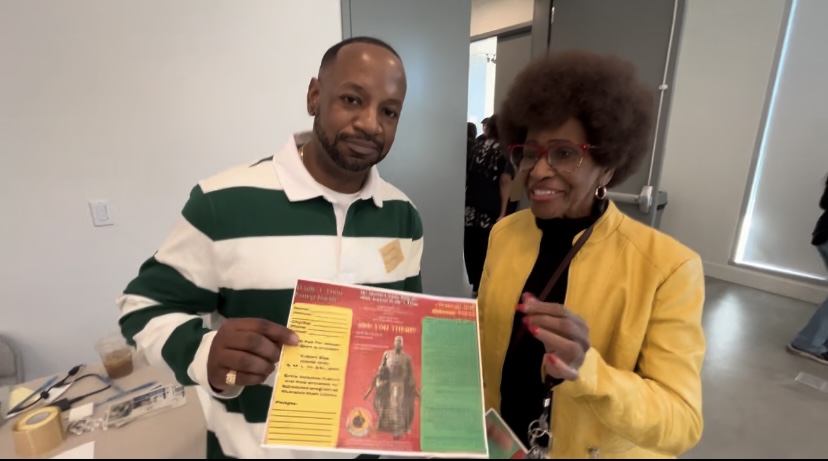

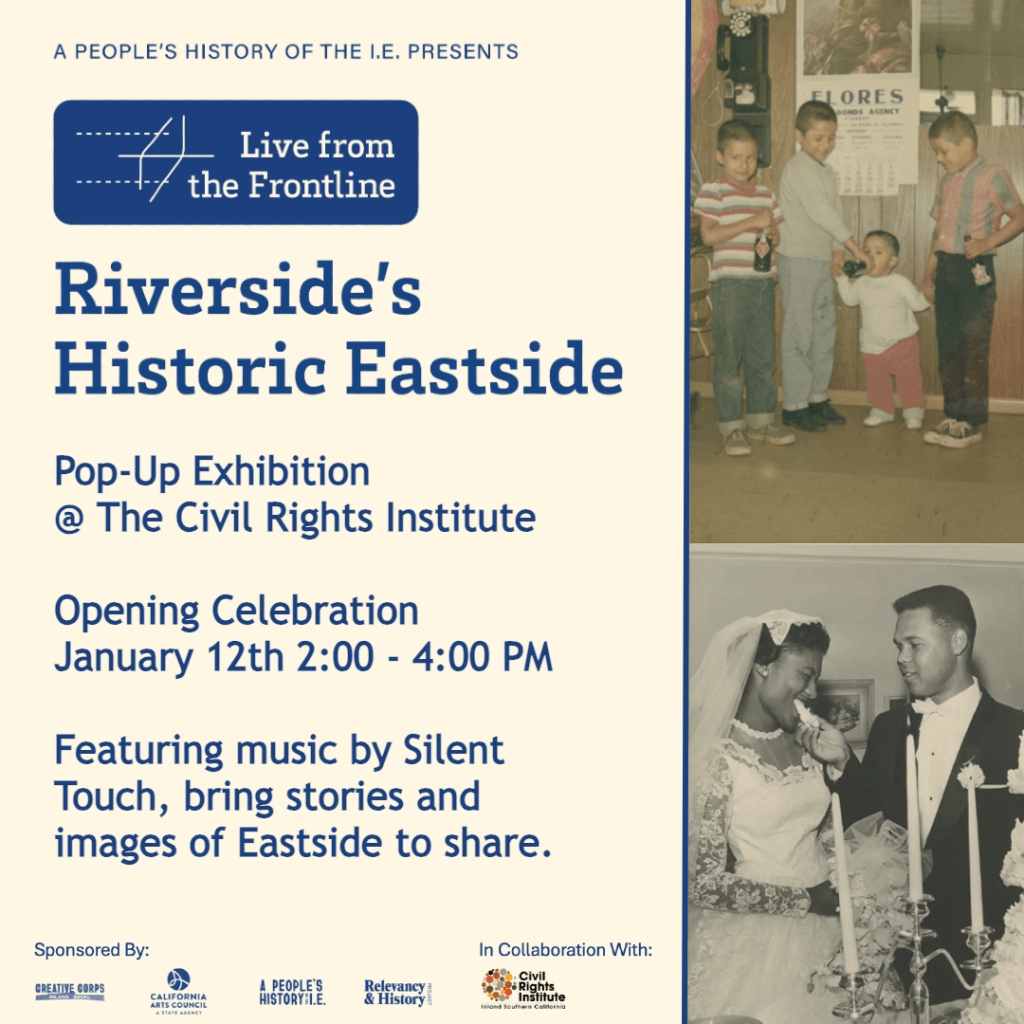

Celebrating the history of the African American community in Riverside’s Eastside

This historical exhibition was a month long celebration. It all began January 12, 2025 at the Civil Rights Institute in Downtown Riverside. Jazz band Silent Touch played their first show together in over 43 years.

The history of Systematic Racism and white supremacy in Riverside, California.

The city of Riverside, California has a long-celebrated history of the Ku Klux Klan and white supremacy that dates to the early 1900s, with the film premiere of Birth of a Nation. The film served as a recruiting tool for the resurgence of the new Ku Klux Klan. This resurgence was due to a socioeconomic cultural shift from rural southern towns to middle class suburban American cities. This new clan did not hide behind white cloaks but wore doctor coats, business suits, and badges that enabled them to blend in society as status quo white Americans. Klansmen took on the image as middle-class white men looking to influence local and state governments. “They relied on fraternal lodges and Protestant churches for support, and often struggled against elites for civic control” (Hudson 2020, p. 173). Riverside served as a perfect safe economic haven for this new emerging Klan. Riverside is the birthplace of the citrus industry while also fostering one of the most active chapters of the Ku Klux Klan in the state. In the 1920’s “The Riverside Klan had twice as many members as the better-known Anaheim Klan” (Hudson 2020, p. 187). Influencing local politics and a promise of strengthening law enforcement. “In 1927, Riverside elected a Klan backed Mayor, Edward Dighton” (Esparza & Moses, 1996). Violent racial relations between African Americans and Caucasians in Riverside continued throughout the 1930’s. At Lincoln Park in 1941, a softball game ended in a near riot between white soldiers and African American soldiers. “In the months afterwards, African Americans became targets of unprovoked attacks, whether walking the streets of downtown or elsewhere” (City of Riverside African American Civil Rights Historic Context Statement, August 2022. P. 19). The only high school in the city was a known recruiting ground for the Klan. One of their most flamboyant recruiting events took place at Riverside Poly High. The event had between 4,000 to 15,000 in attendance at the football stadium where 217 new members were inducted into the Ku Klux Klan. “A fiery cross was pulled across the sky by a small airplane just as dusk settled over the high school” (Hudson 2020, p. 183). The Klan was not hiding in Riverside, and they wanted it to be known. Witnesses to the event described the showmanship as a pageantry, and one of the greatest crowds ever seen in Riverside. “An advertisement for the parade claimed that the members of the Riverside Klan were of the highest standing…ministers, doctors, lawyers, bankers, merchants, former service men- in fact Real Men from every walk of life” (Hudson 2020, p. 185). The Ku Klux Klan was known for bombings and for making threats of bombings. Ray Wolfe, a reporter for The Riverside Press-Enterprise was threatened that his office would be bombed if he printed a story about the Ku Klux Klan after they stormed into a local African American church. For the intention of intimidation during church service, Klansman walked down to the front of the church then walked out.

Racially restrictive housing covenants- Irving School was built on the corner of Victoria and 14th street in 1891. It was integrated as Anglos were the majority population in Riverside, California. African Americans began settling in the city’s Eastside neighborhood of Riverside by 1900. In the area north of University Avenue (8th street). African Americans faced unofficial discrimination and segregation in the city. In 1907 the Riverside City Charter became the Riverside City School District accepted de facto segregated neighborhood schools. Lowell School opened in 1911 south of 14th street to serve the white community. Because of racial tensions and the fear of rising race riots in Riverside, California, restrictive racial housing covenants began spreading in the city. By 1917, zoning and racially restrictive covenants restricted the future sale of property to African Americans. The Victoria Association and The Castlemont Tract (Wood Streets) were known covenants in the city. Agreements were made between homeowners and buyers, real estate agents and neighbors to continue segregated neighborhoods. By the late 1940’s the Eastside was rezoned from single family residences to multi-family units. White flight occurred as more African Americans began moving further north on 8th Street (University Ave) between 8th and Blaine and south of 14th street. Restrictive racial housing covenants remained throughout the mid 1950’s as more than 210 new housing subdivisions were constructed in the city. “By 1952, at least half of the houses in Riverside contained racial restrictions, limiting their sale to Caucasians” (Storymaps). In 1956 the Riverside Daily Press wrote “Riverside neighborhoods were closely fenced in by “Gentlemen’s Agreements’ that aim to keep people of color out of primarily Anglo neighborhoods” (Riverside Daily Press, 1956). Because of racially restricted neighborhoods, the schools in those neighborhoods were also racially segregated. By the 1950’s African American and Latino students made up majority of the student bodies of both Irving and Lowell school. White parents were angry at the growing number of minority students. In 1960 the minority population of Lowell jumped to 90%. The Superintendent recommended open enrollment instead of integration in 1961. In 1965 parents meet with RUSD to petition for integration holding a drive. That September a week before school began Lowell School was mysteriously burned down by an arsonist or angry parents.

Destabilizing the community– In 1971, social and cultural capital was practiced amongst the African American community in the Eastside of Riverside in the form of social groups and religious groups. Reverend John H. (Shabazz) Morris ran the Shabazz Market and Muhammad’s Mosque on Park Avenue. “He oversaw a group of Black Panther Party (BPP) members from San Diego at Riverside People’s Center nearby (4046 Dwight Ave.), who operated a Free Breakfast Program for children and distributed a weekly BPP newspaper” (Storymaps). Out of fear of the reputation of violence from the Black Panthers, the Riverside Police Department raided their house on Dwight Ave. “On the night of April 2, 1971, Police Officer Leonard A. Christiansen and his partner Paul C. Teel responded to a burglary call. As their vehicle pulled into the driveway, hot bullets exploding from steel barrels shot out from the darkness” (Kira Roybal, Staff writer). The two officers passed away after they were ambushed while on duty in Riverside, California, United States. Police believed that the work was carried out by three Black militants. Black Civil Rights leader Gary Lawton, Nehemiah Jackson, and Larrie Gardner, were tried three times for the murders, but were never convicted. Because of this crime, any African American male in this community that is suspected of being a Black militant of Black Nationalist is subjected to police investigation, questioning, and harassment. Following this horrific crime the Riverside Police Department has racially profiled the entire African American community that makes up the Eastside of Riverside.

The African American community that makes up the Eastside of Riverside has been falsely labeled as people who hate the police enough to murder. Which is not true. As a result, this community is patrolled by law enforcement agencies more than any other area of the city. This community is underfunded due to a lack of economic opportunities and resources. The disenfranchisement of this community has attributed to the high numbers of poverty, crime, low income, low graduation rates, food disparities, drug addictions, and mental health issues due to the systemic racism this community has undergone.

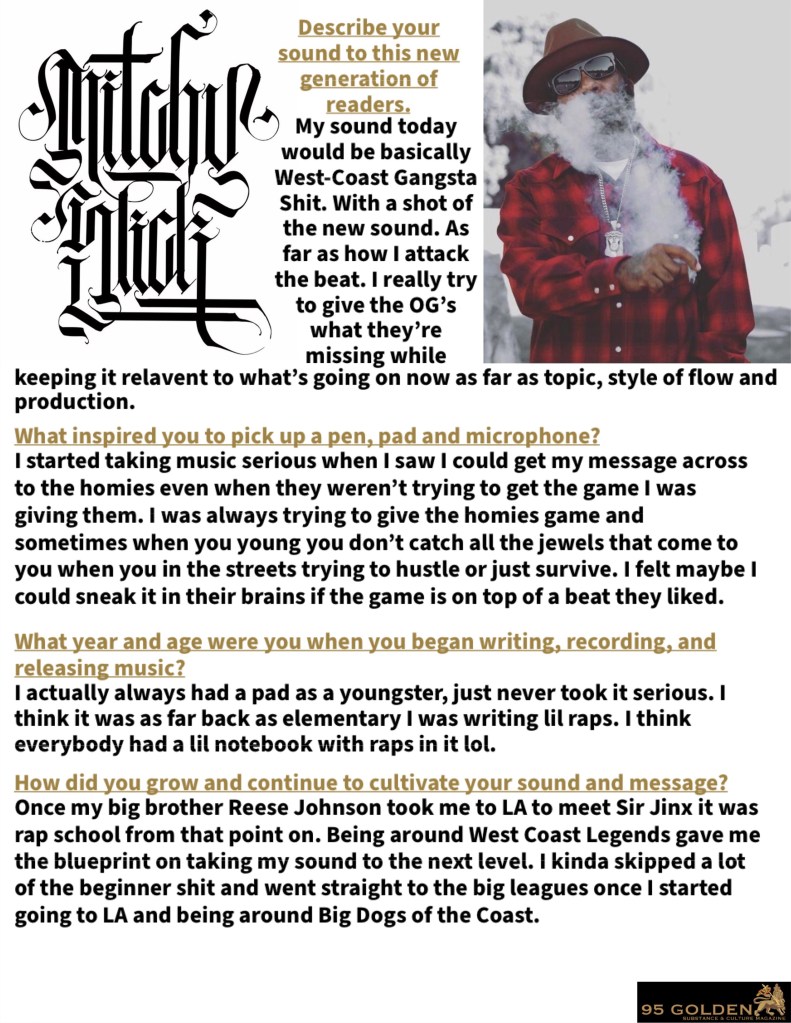

95 Golden Classik Artist Spotlight interview with West Coast Gangsta Music Pioneer Mitchy Slick

To me OG means Original. OG is an individual who has gained wisdom through their life experiences. The game they sprinkle lil homies with make OG’s true living legends. Real OG’s are more than down to reason with lil homies. So that they don’t repeat mistakes that can cost them their lives. Because most out here do not play fair. Through hip-hop music and my Southern California lifestyle Mitchy Slick gave me an audio/visual tour to and through his South East San Diego neighborhood of Lincoln Park, right there in the projects on Logan Ave. The stories to me are about a young Black man. One who makes it to the other side. To live and see the fruits of his labor. Which is success by defeating the odds in America. Some of the stories were about victories he has had while navigating his life in a warzone. The stories Mitchy Slick shares not only turned me up through the roof, but also gave me goosebumps at an early age. The stories are also indoctrinating to me at the same time. Some things I have taken note to is that there is going to be some hustling you need to get done in order to make your money work for you. Instead of the other way around. However, whichever way you decide to get that money or how it comes to you is your choice. So remember slow and low is always better than show or no. Nuff said. Respect this classik 95 Golden artist spotlight interview with West Coast Gangsta Music Pioneer OG Mitchy Slick.

Thrive DaSun live interview & performance on The B-Side Show Live!

This filming of the B-Side Show took place on Martin Luther King Jr Day Monday January 21, 2020. The B-Side Show was celebrating 10 years of being a service to Hip-Hop Music & Culture. The B-Side Show is live streamed every Monday night on their YouTube channel. Big Ups to Rabbit, Shay & Deejay Nimfo

The B-Side Show is streamed live every Monday night on their YouTube Channel.

Nanlibinvasion is the culture

Grime and the drip culture with Richie aka Deladeso

95 Golden Artist Spotlight SHRXXM

Rocking with Thrive live on the China Show!

China Williams is one foxy gal indeed. She is bubbly plus upbeat. Need to mention her sizzling aura that only lets groovy vibes around her. So make sure you sage and musk the room before inviting her over for a conversation over mimosas plus acrylic paints. This was China and Thrive’s first time meeting. If you know Thrive. Then you must already know the difficulty of getting him to open up and relax a little. When he finally does open up and speak. He may or may not say the right thing. However, doing the right thing is always more important than saying. This filming of the China Show was filmed 9 October 2020 at Street Rat Studios in the Shitty City. We all know how “this world” changed rapidly with the falling of Babylon. So I&I gives Thanks to God for Zion. Nuff said….